In everyday life, we use the word love to talk about many different things. It might mean a strong emotion, closeness, trust, the sense of being connected, or simply that we really like someone.

The word becomes a kind of umbrella for experiences that feel good, important, or deep. The stronger the feeling, the more likely we are to call it love—even if it doesn’t last very long or isn’t felt the same way by both people.

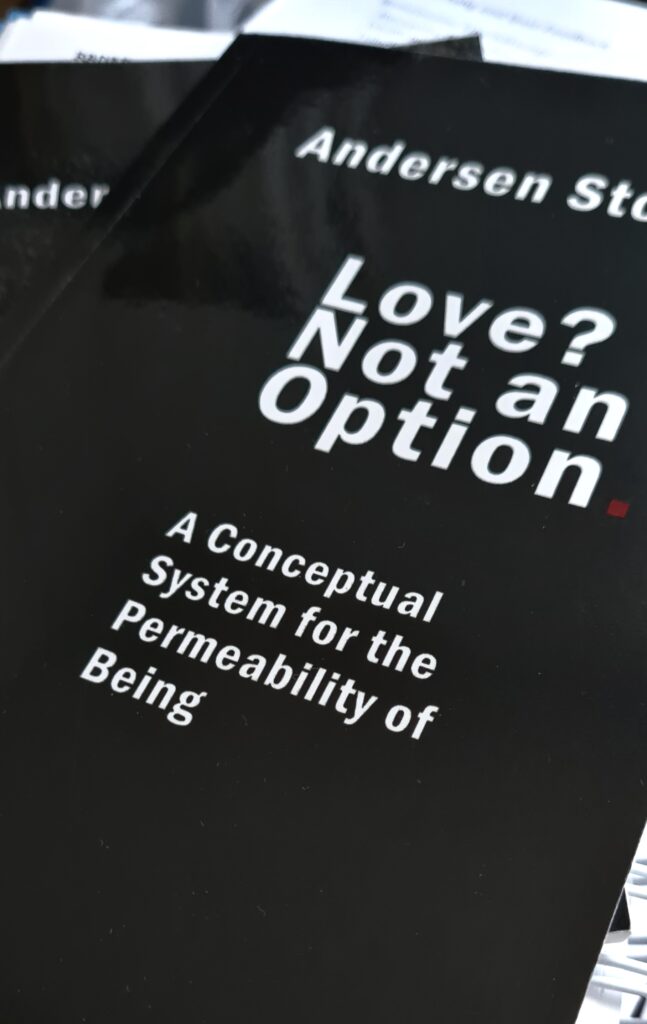

Why Love – On Resetting an Overloaded Word | ausderLiebe

In this everyday sense, love is often said to show how

much someone means to us.

The phrase “I love you” is meant to express:

“You are very important to me. I want to be close to you.”

This feeling is real—but the word love is being used

for many different things at once.

1.

Love is unbroken.

But the word meant to bear it—

bears too much:

too much feeling,

too much history,

too much grip.

In the conceptual system of the book,

love means something entirely different.

It’s not a feeling and not a relationship between people.

Here, love refers to the field in which everything can begin.

It’s the condition that makes experience possible at all.

It’s what allows anything to happen,

what makes connection and encounter possible.

2.

In speaking,

the word loses its edge.

Love comes to mean relation,

morality, need, a longing for closeness—

or for control.

All at once.

No longer whole.

This kind of love isn’t something we choose, divide, or lose.

It’s not a feeling—it’s what makes feelings possible.

It’s what holds everything.

3.

The symbol softens—

for those who fill it

with purpose:

as commodity,

as power,

as justification.

When people feel love in everyday life,

that feeling is not wrong.

But in the conceptual system,

that feeling is not the same as love itself.

It’s seen more as an echo—a moment

in which someone comes close to the deeper field

that carries us. It’s a real and important experience,

but it’s not the field itself.

4.

“I love you” can then mean:

“You belong to me.”

“Stay.”

“Forgive.”

“Consume yourself for me.”

That leads us to this key difference:

In everyday life, love often means the feeling

of being carried.

In the conceptual system, love is what carries—

even when we don’t feel it.

5.

When the work states:

Love is not a feeling—

it does not pass

judgment on feeling.

It protects only what

must not be confused.

This difference isn’t meant to confuse, but to clarify.

It shows that our feelings are meaningful,

but they’re not everything.

And it opens the idea that love might mean more

than we usually assume.

6.

This system does not speak from lack.

It speaks from quiet order:

Love is not a solution. It is a precondition.

So in the conceptual system, love isn’t something

we say or do—it’s what makes it possible for

two people to meet at all.

But when someone says “I love you”, they’re expressing

something real in everyday terms. A moment of closeness,

of meaning, of wanting to be near.

That feeling is true—it matters. Even if it’s not

the field itself, it can be a sign of being near it.

7.

It separates—in order to restore distinction:

between where something is carried,

and where it is merely held.

8.

Love does not need defense.

But the word requires

reconnection—

so it can no longer be used

to bind

where nothing sustains.

© 2025 Andersen Storm